Briefing 4

Agri-SMEs operating in uncertain financial, operational, and supply chain conditions: Pathway 4

- 4.1 Pathway 4 Overview

- 4.2 The External View: Understanding the impacts of disrupted markets on agri-SMEs

- 4.3 The Internal View: Managing agri-SME challenges to survive a prolonged shock

- 4.4 The Long-Term View: Responding now to mitigate longer-term market impacts

- 4.5 Moving Forward: How governments, donors, and service providers can best support this pathway

Pathway 4 businesses range from commercial farms to small and medium agricultural enterprises (agri-SMEs) such as input suppliers, agro-dealers, cooperatives, traders, and processors. They are formal enterprises that typically rely on hired labor and mechanization. These enterprises are the lifeblood of agricultural value chains and local food security. In Africa, it is estimated that agri-SMEs sell 80% of the food produced for local consumption and generate 25% of rural employment. Despite their importance, it’s very challenging for commercial farmers and entrepreneurs to access financing, since financial service providers often consider them high risk and higher cost to serve. In fact, in sub-Saharan Africa alone, a Dalberg and KfW report estimates that there is a $100 billion lending gap for agri-SMEs. Lack of access to financing means that agri-SMEs* are particularly exposed to changes in demand or operations—such as those resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The impacts of COVID-19 on these businesses are likely to be felt all along the supply chain, from producers to consumers, with significant long-term consequences for rural livelihoods and food security.

*For ease of reference, commercial farms that meet Pathway 4 criteria will be referred to as agri-SMEs in this briefing, unless otherwise specified.

Pathway 4 businesses rely both on the steady demand for their goods and services, and the provision of goods, services, financing, and information to their business. The COVID-19 crisis is disrupting both of these critical needs.

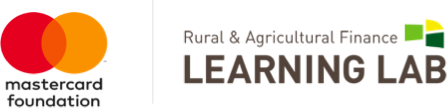

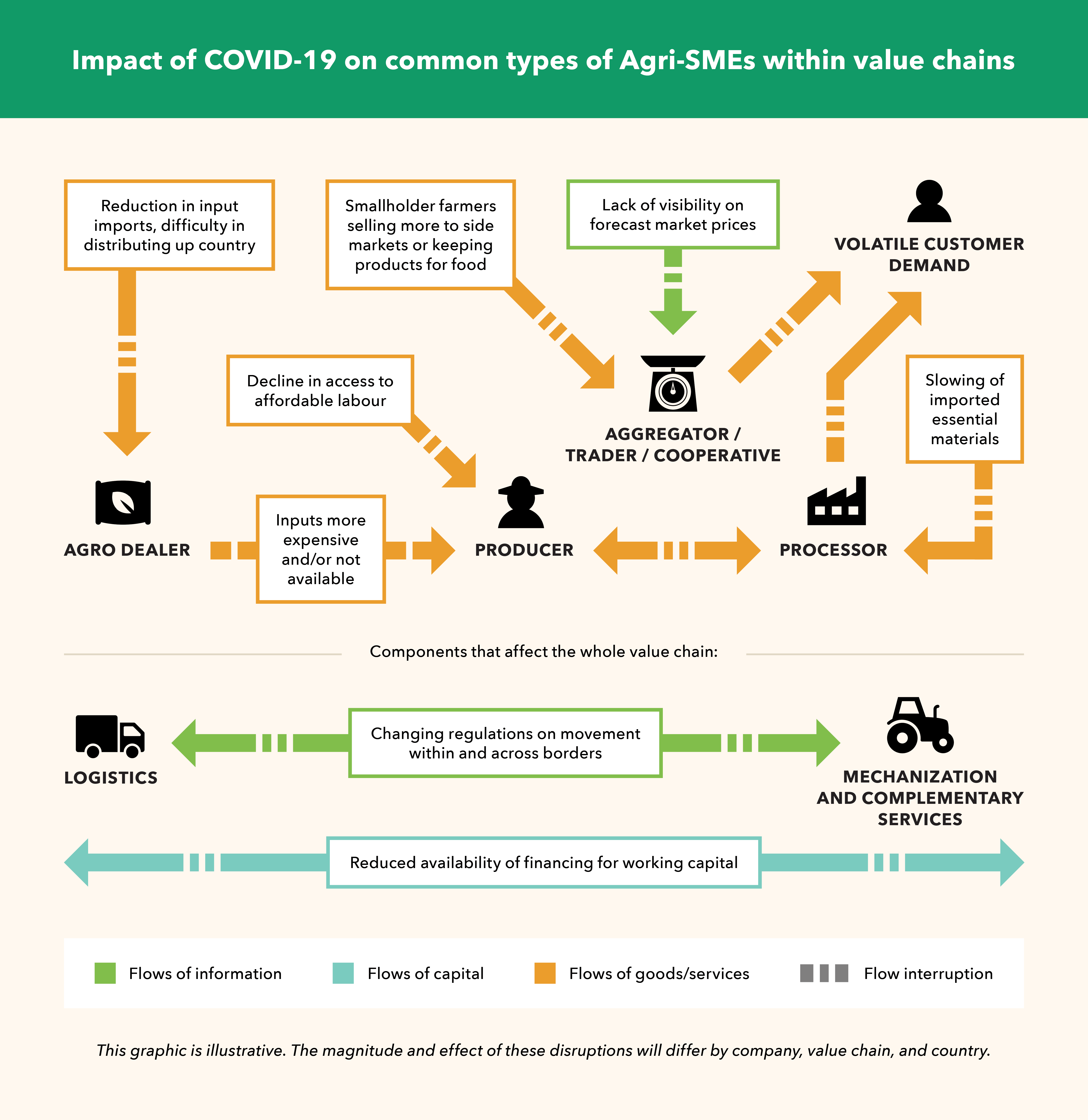

Across value chains, the biggest impact of COVID-19 on agri-SMEs is changes in demand, followed by disruptions to the flow of goods, information, and capital. Some businesses may benefit from increased demand for staple goods—but, for many, the supply chain disruptions will have a negative effect. The graphic below shows how typical COVID disruptions can impact Agri-SMEs.

Volatile demand for products is disrupting the ability of agri-SMEs to maintain their businesses, across all types of value chains.

Starting with demand:

- Shifting consumer demand from international markets. While the health risks of the pandemic reached developed economies first, changes in international demand for agricultural goods were felt immediately in emerging markets.

- Decline in local demand, due to restrictions and loss of income. Changes in demand are also noticeable in local markets, driven by both decreased incomes and social distancing regulations.

- Resulting price volatility. Prices of goods have been very volatile as demand for different types of food continues to change. In general, the price for staple goods has increased with demand. These price fluctuations make it very difficult for agri-SME to forecast and manage their cash-flow which in turn has a significant effect on financing their operations and servicing any financing commitments.

The flow of goods and services:

- Flows of inputs. The supply and distribution of inputs for agri-SMEs has been severely disrupted by both international and domestic travel restrictions. This includes inputs such as seeds and fertilizer for commercial farms, and raw materials for processors.

- Labor availability. The travel restrictions and risk of the virus have also impeded the availability of labor, a crucial factor in agri-SME operations. Travel restrictions, limits to public transport, and curfews have all forced changes to labour use—varying based on the severity of the government interventions and the density of labour needed for the business’ operations.

The flow of information:

- Understanding public health requirements. Governments have issued public health guidance writ large, but guidance for essential services is not always clear. In transporting goods, agri-SMEs fall into a grey area. In some cases, security services don’t recognize agri-SMEs as “essential service,” which leads to additional unnecessary delays.

- Clear market information. Access to market information is an existing gap for many agri-SMEs. With the arrival of COVID-19, and the corresponding volatility in demand and supply of products, this information gap is even more apparent. Farmers may be in touch with traders and suppliers, but do not have the information to plan or forecast for the future. Some are holding off on investments for next season while they await more information—which will significantly impact next season’s harvest.

- Becoming aware of support options. Some governments have provided support for small businesses, but it is typically focused on reducing taxes and providing loan extensions via central banks. There are a number of opportunities for SMEs being provided by NGOs and development finance institutions (DFIs).

The flow of capital:

- The existing financing gap was already significant. In sub-Saharan Africa alone there is a $100 billion lending gap for agri-SMEs. This is partly driven by the higher cost to serve agri-SMEs, which is driven by small ticket sizes and the higher risk profile. Financing challenges are even more severe for women-owned SMEs, of which an estimated 70% have inadequate or no access to financial services. For women, lower rates of savings, lack of networks, discrimination, and social norms can pose additional challenges to securing the capital needed to grow or expand their business.

- COVID-19 is creating even more financing pressure for agri-SMEs. Volatile markets and ongoing restrictions of movement are putting additional pressure on agri-SMEs’ finances. Central banks in some countries are looking for ways to support SMEs, but the measures have not been sufficient. In Kenya, the Central Bank has directed SMEs to contact their banks for assessment and restructure of their loans, but the system can take weeks to process; many agri-SMEs cannot wait this long.

- While many commercial banks stage a retreat. Banks are facing challenges in serving customers as their own credit lines are constrained, particularly for foreign currency. As international demand contracts for exported cash crops, countries that rely on agriculture exports may see a decline in foreign reserves. This, in addition to the currency devaluations being seen across the world, could decrease the ability of countries to import essential supplies.

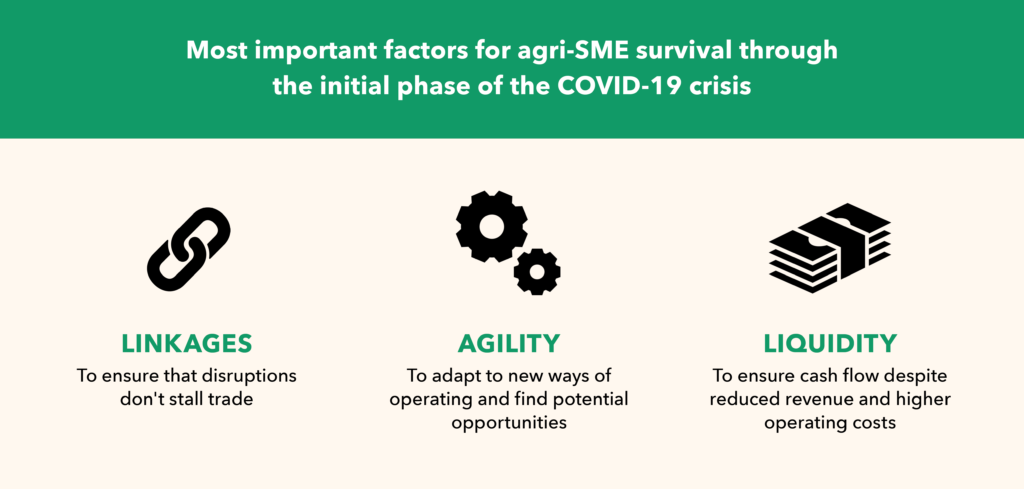

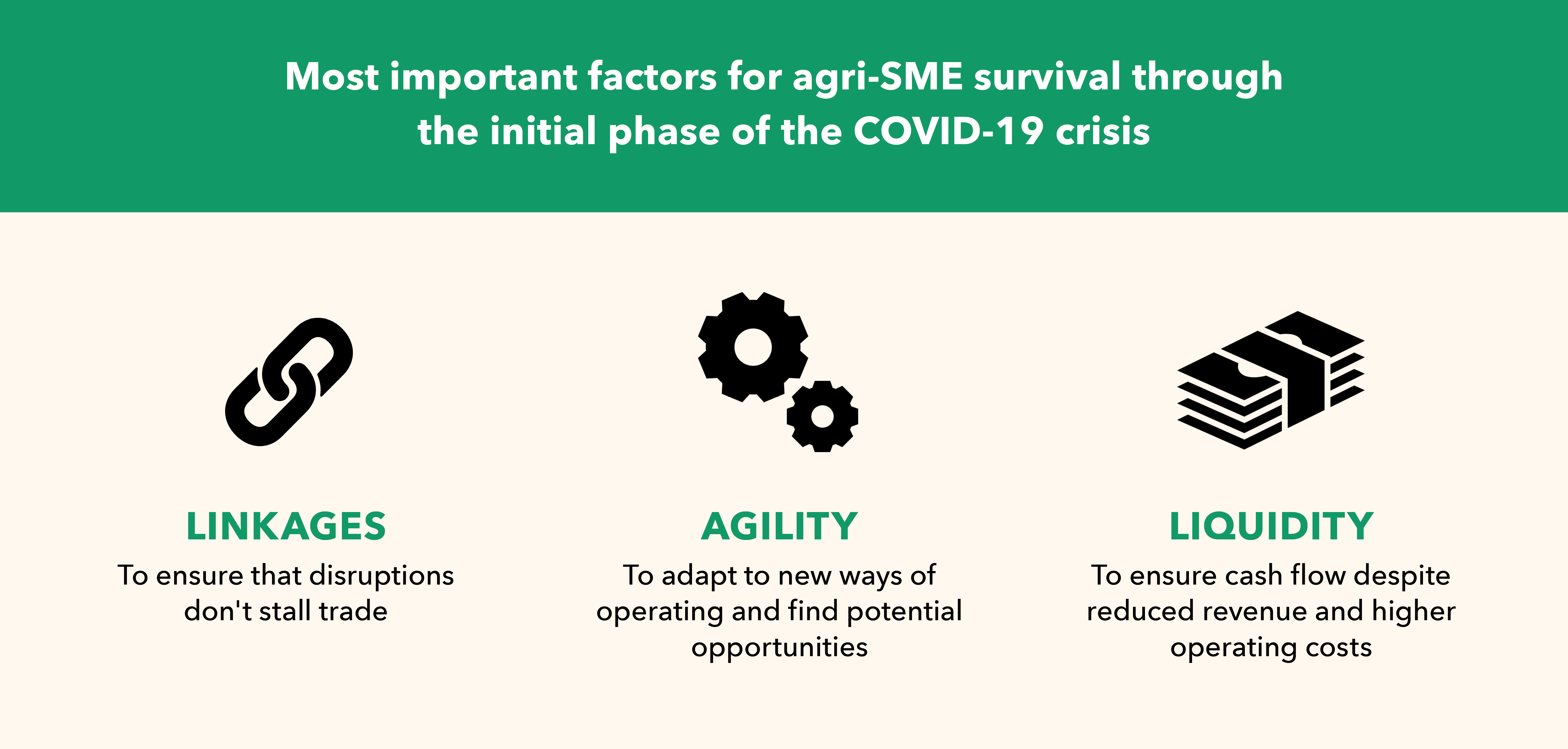

In the short-to-medium term, agri-SMEs must focus on surviving the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, a challenge that centers around how they manage disruption of linkages, create agile responses, and manage their cash reserves.

For many agri-SMEs, the COVID-19 crisis is an existential threat. Findings from a USAID-sponsored ACDI/VOCA survey in Honduras found that 83% of enterprises will close their operations within three months if the situation does not change (31). Whether enterprises survive the crisis will be heavily dependent on their balance sheet, ownership structure, contracts, location, and systems. Agri-SMEs have different starting points that will heavily influence their ability to pivot into new opportunities. However, three factors are likely to be most important to agri-SME survival through the initial phase of the COVID-19 crisis: linkages, agility, and liquidity.

Linkages:

- Agri-SMEs are highly interdependent actors in agricultural value chains, meaning any disruption has immediate consequences. Agri-SMEs depend heavily on the continuous flow of goods and services — what we call functional linkages. These linkages broke very quickly in the face of social distancing measures, transport restrictions, and consumer spending decreases. Traders, aggregators, and transporters — agri-SMEs sitting at transitional points in the value chain — were hit first. Very quickly, however, their inability to operate led to bottlenecks more broadly.

Agility:

- To mitigate the risk of broken linkages, agri-SMEs need to adapt quickly to new circumstances, potentially changing fundamental parts of their business. Like businesses around the world, many agri-SMEs have had to adjust their operations to comply with social distancing regulations, provide PPE, and keep their teams safe. In other cases agri-SMEs may be forced to “hibernate” or close their business completely. In countries with extreme lockdown measures, some larger processors have even provided accommodation for their staff. These types of measures, while safer, increase operating costs and may unintentionally exclude women if they have caregiving responsibilities or are not permitted to work away from home.

Liquidity:

- The breakdown of strong linkages — particularly demand — makes agri-SMEs even more reliant on difficult-to-access commercial financing for survival. Agri-SMEs are historically underserved when it comes to commercial financing. This lack of financing will almost certainly be exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis—right when agri-SMEs need access to financing the most. Most agri-SMEs do not have the balance sheet to continue their operations in the face of extended decreases in revenue and increases in compliance costs. The most vulnerable agri-SMEs are the already under-capitalized smaller or less established businesses that will continue struggling to find formal financing. These SMEs tend to be in more remote areas, which makes it more difficult for them to access and complete loan assessments, even without restrictions on movement. These are the businesses that urgently need liquidity in order to keep their operations going, and keep food moving through the system.

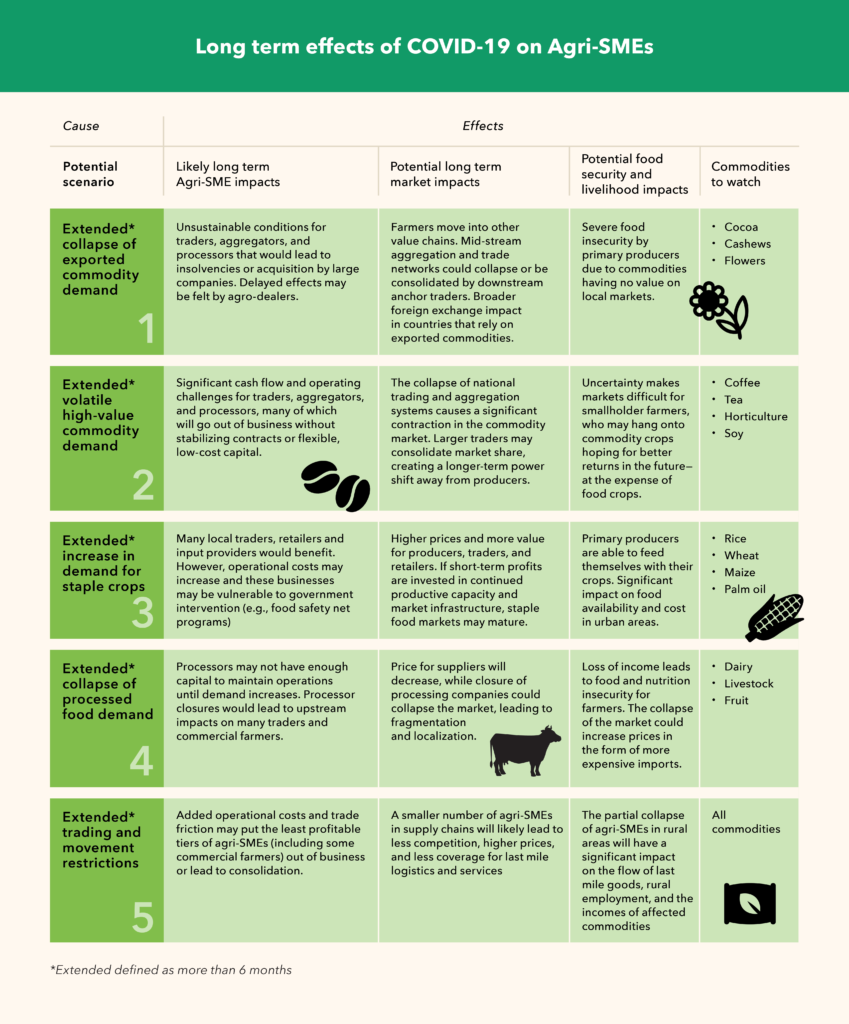

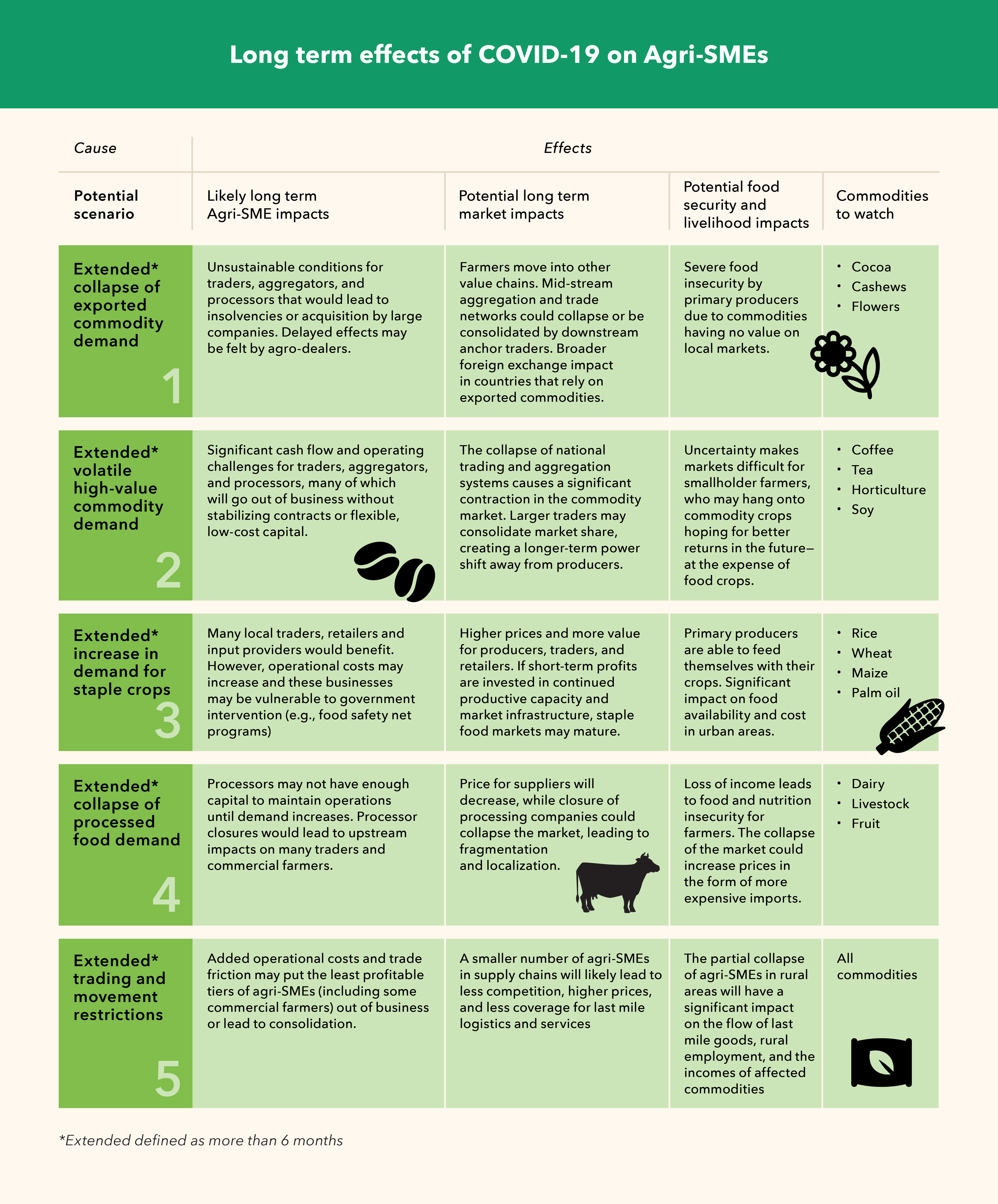

It is not yet clear how agricultural value chains will be shaped by COVID-19 in the long term. However, as outlined in our initial Emergency Briefing, the potential cascading effects from rural livelihoods to markets to food security and ultimately national security are critical to understand.

Without sufficient action now, the wholesale failure of rural agri-SMEs risks to, at best, cripple national commodity markets, and at worst lead to their complete collapse.

The survival of agri-SMEs has high stakes. With tourism collapsing, many countries will be forced to rely even more heavily on agriculture — both to feed their own population and to generate highly sought-after foreign exchange to enable central banks to continue to service their debt obligations and maintain the liquidity needed to import necessary goods — particularly important to economies that rely on staple food imports. The five illustrative scenarios below project what might happen to agri-SMEs, markets, and livelihoods if sufficient support is not provided throughout the COVID-19 crisis.

While the scenarios above are dire predictions, there are also opportunities for agri-SMEs. The many agri-SMEs that do survive can build back better with:

- More agility: The crisis will make many agri-SMEs more agile, as they are forced to adopt new technologies, potentially increasing digitization and spurring broader rural digital technology usage. These enterprises may find new input suppliers when the regular supply chain is delayed. They may also pursue new business opportunities, including distribution channels, product offerings, and customers. Some may form partnerships with other businesses, ultimately strengthening their own business model.

- More flexible finance options: Investors will change their needs assessments or find more effective ways of conducting them with social distancing—potentially even lowering the costs of operations and therefore increasing the potential for profit. Similarly, investors may speed up their process due to the urgency of the pandemic. Some may change their requirements in recognition of the unique situation and the collapse of other national industries, such as tourism. There is a particular opportunity at this juncture to embed a gender lens throughout the investment process, and set ambitious targets for financing youth-owned agri-SMEs, bringing inclusion to previously unbanked or underbanked business owners.

- Greater resilience: Investors are likely to refocus their efforts with agri-SMEs on resilience: the business’ ability to bounce back from a crisis. The CDC Group, for example, has stated that its investments will prioritize resilience, resource efficiency, adaptation, and ability for businesses to withstand future shocks. This provides an opportunity for agri-SMEs to rise to the challenge of investors, and local financial institutions to rise to the challenge of serving agri-SMEs.

Agri-SMEs are vital to agricultural markets: they facilitate trade, keep people employed, and enable food security. To ensure they continue to operate throughout and beyond the pandemic, it is critical that we invest in maintaining their linkages, increasing their liquidity, and supporting their agility.

PITFALL #1: Underestimating the potential for catastrophic long-term costs and large-scale failures of agri-SMEs.

- ACTION NEEDED: Governments will need to take the lead on rapid scenario planning to ensure the scale of the agri-SME challenge is understood and defined. Any upfront investment (however large) should be weighed against the longer-term costs (to employment, rural incomes, food security and trade) should large numbers of agri-SMEs fail.

PITFALL #2: Relying on current models of agri-SME financing to step in without creating more effective, faster ways to deploy funding to the right places.

- ACTION NEEDED: Governments, donors and impact investors will need to rapidly bolster commercial bank lending to agri-SMEs through risk-sharing mechanisms and relaxed regulatory requirements where appropriate; while at the same time using less traditional financing channels including fin-tech models and direct government programs to get credit flowing.

PITFALL #3: Failing to prioritize and target the most critical value chains for food security, and the most vulnerable points of dependency within those value chains.

- ACTION NEEDED: Governments need to identify critical value chains for food security (including those that earn foreign exchange for food imports) and find ways to support the most vulnerable linkages through program support, regulations, or cash injections.

PITFALL #4: Assuming technology is a simple solution for agri-SMEs.

- ACTION NEEDED: Donors and service providers who are working to bring technology systems to agri-SMEs need to be careful about how and where technology is applied.

PITFALL #5: Missing the opportunity to shape more resilient and inclusive markets, even as some businesses fail.

- ACTION NEEDED: Governments and donors should be thinking outside of the box in terms of how the pandemic could lead agri-SMEs to build back better within more resilient and inclusive food systems.