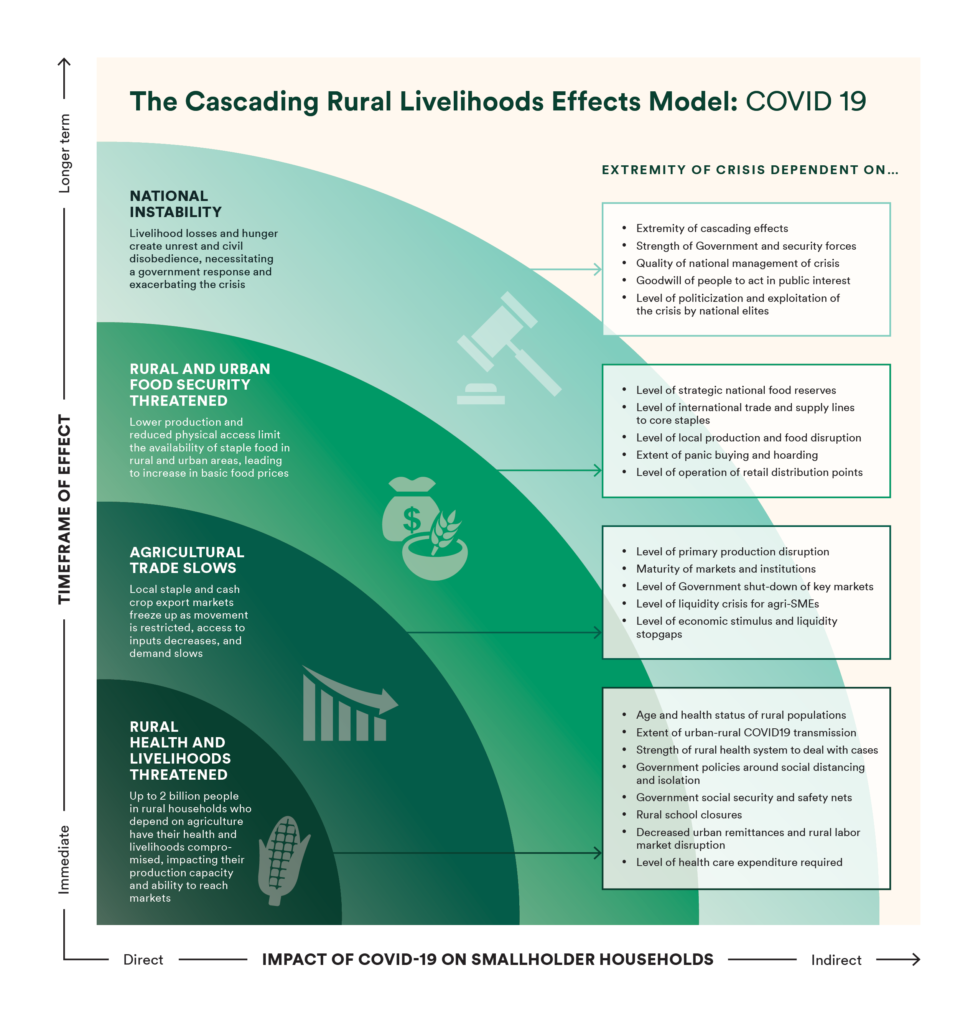

With so many intersecting issues that will play out differently across countries, we believe that it is useful to consider how outcomes cascade from the rural poor to agricultural markets to food security and finally to national stability.

For rural households the impact of the virus will likely be first felt in compromised livelihoods. This is both from agriculture, with local retail markets closing, and from households’ additional income streams of remittances, urban migrant work, or other additional businesses slowing or stopping. More commercial farmers will be affected by slowing agricultural trade more broadly, particularly with less access to inputs and financing that will affect the next harvest season. The health impact however cannot be overlooked or understated. Rural households are particularly vulnerable to the health effects of the virus as they are less likely to have access to healthcare facilities with oxygen and ventilators. This is compounded by the fact that any added financial shocks of hospital admission or funeral costs for rural households can be devastating.

In agricultural markets any effects to rural household health and livelihoods may impact production directly, decreasing planting and harvesting. Further, social distancing and border closures will impact production and transportation, while changes in spending power of consumers will impact demand. Market linkages are particularly at risk, as food systems adapt to different ways of working and demand patterns. Limited access to inputs due to decreased distribution and financing will affect yields of future harvest cycles, even after the immediate risk of the virus has passed. Transportation has already been significantly affected, which has ramifications on market linkages. By sea, less cargo is being processed due to fewer ships and decreased capacity of ports. By road, curfews and geographic restrictions (both within countries and across borders) have slowed road transport. Within agricultural markets, agri-SMEs that keep agricultural markets moving are particularly at risk as credit lines slow down and operations are disrupted.

With national food security there is a risk of disrupted supply of food from the affected local, regional, and global agricultural markets. While the FAO continues to reassure its members that there is sufficient food globally, the distribution of this food is impeded by national policies designed to contain the virus. This is particularly dangerous for countries that are net-importers of staple foods. Many rural households, especially those living in or at the threshold of poverty levels, are subsistence farmers. If the virus affects their ability to farm and produce their own food, there will be a significant increase in emergency food needed from government or other aid organizations. For commercial farmers this risk goes even further, potentially disrupting the food security of urban populations. It must also be noted that in some areas food insecurity is already at risk due to natural disasters such as drought and locust infestations. Food security in many developing countries is already in fine balance, and any disruption to rural livelihoods and agricultural systems can quickly create large populations of food insecure people.

National stability is related directly to the disruption of so many livelihoods (both rural and urban) and subsequent impacts on food security, and could quickly escalate into social and civil unrest. As families become hungrier and more people are directly impacted by the virus there is a risk that people will turn to violence or other illegal activities to survive. This is particularly dangerous in areas with active extremist groups who already use food insecurity as leverage to gain support. In addition, the use of food security as a lever for political gains may further destabilize countries, particularly where there are upcoming, or delayed, elections.