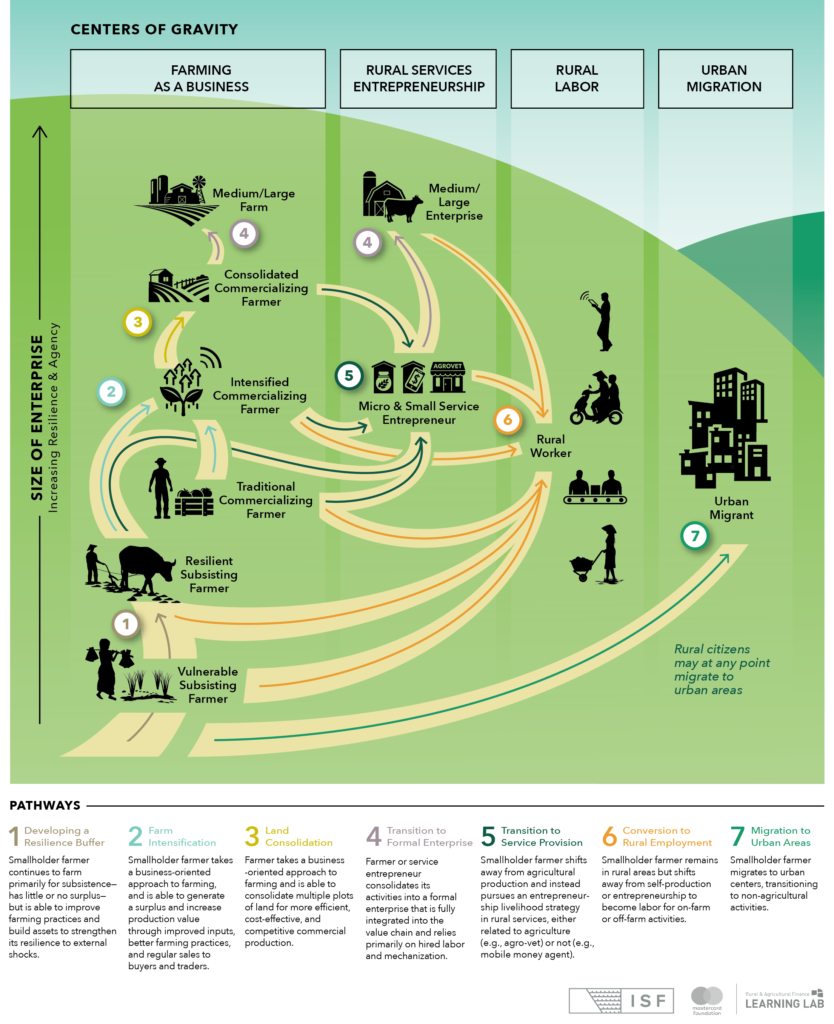

A new rural pathways model moves us from a static understanding of smallholder households based on their characteristics at a particular moment, toward a dynamic view of how households might evolve over time and how their needs change as they move along different development trajectories. The model lays out the different transition pathways smallholder households may take as they pursue increased resilience and agency through various livelihood strategies. These transition pathways coalesce around four centers of gravity — broad categories of livelihoods that rural households may choose to engage with:

- Farming as a business: Smallholder households remain in primary production. As a smallholder household invests in growing its farming business, it may move from subsistence to more intensified or commercialized farming. Households in this category may eventually transition into a medium or large farm enterprise.

- Rural services entrepreneurship: Some smallholder households may shift away from primary agricultural production, pursuing entrepreneurship-based livelihood strategies. They may focus on agricultural services (e.g., inputs, veterinary services, processing, or aggregation) or non-agricultural services (e.g., transportation, running a local shop). Micro and small entrepreneurial ventures may eventually grow into medium and large enterprises.

- Rural labor: Households may remain in a rural area but focus their livelihood strategy on employment that supports the activities of large commercial farms or SMEs. This labor may be agricultural or non-agricultural, formal or informal.

- Urban migration: Facing enough push and pull factors, a rural household may migrate to an urban area and transition fully to non-agricultural livelihood activities.

It is important to note that, over the course of a lifetime, there will be both forward and backward movement along these pathways. A single household may also change pathways or simultaneously pursue multiple pathways as they adapt to changing priorities. In many of these pathways, rural SMEs may play a vital role. These enterprises can be started by local entrepreneurs moving along pathways #4 or #5, or by urban entrepreneurs who move to rural areas to set up enterprises that provide employment opportunities for those on pathway #6. Thus, the rural pathways model doesn’t just illustrate choices and behaviors on the smallholder household level but offers insights relevant to rural economies as a whole.

![]()

Why this new perspective matters

The goal of successful financial inclusion strategy is not a single interaction, but rather a long-term engagement that allows smallholder households and agricultural SMEs to improve their economic standing over their lifetime. For financial service providers, this is closely tied to the concept of “customer lifetime value,” where profitability is increased by a relationship that endures and matures over an extended period of time.

By examining the transition points along these pathways, we can begin to understand how a smallholder’s use of financial services and products may change over time. This dynamic understanding will help financial service providers and donors tailor products, bundle offerings, and better communicate with their clients. Perhaps the most striking aspect of the dynamic model is the simple recognition that many rural households will not remain smallholder farmers at all. Therefore, delivering inclusive economic development over time will require a wider range of non-agricultural products and services.