Climate Change and Agriculture in Context

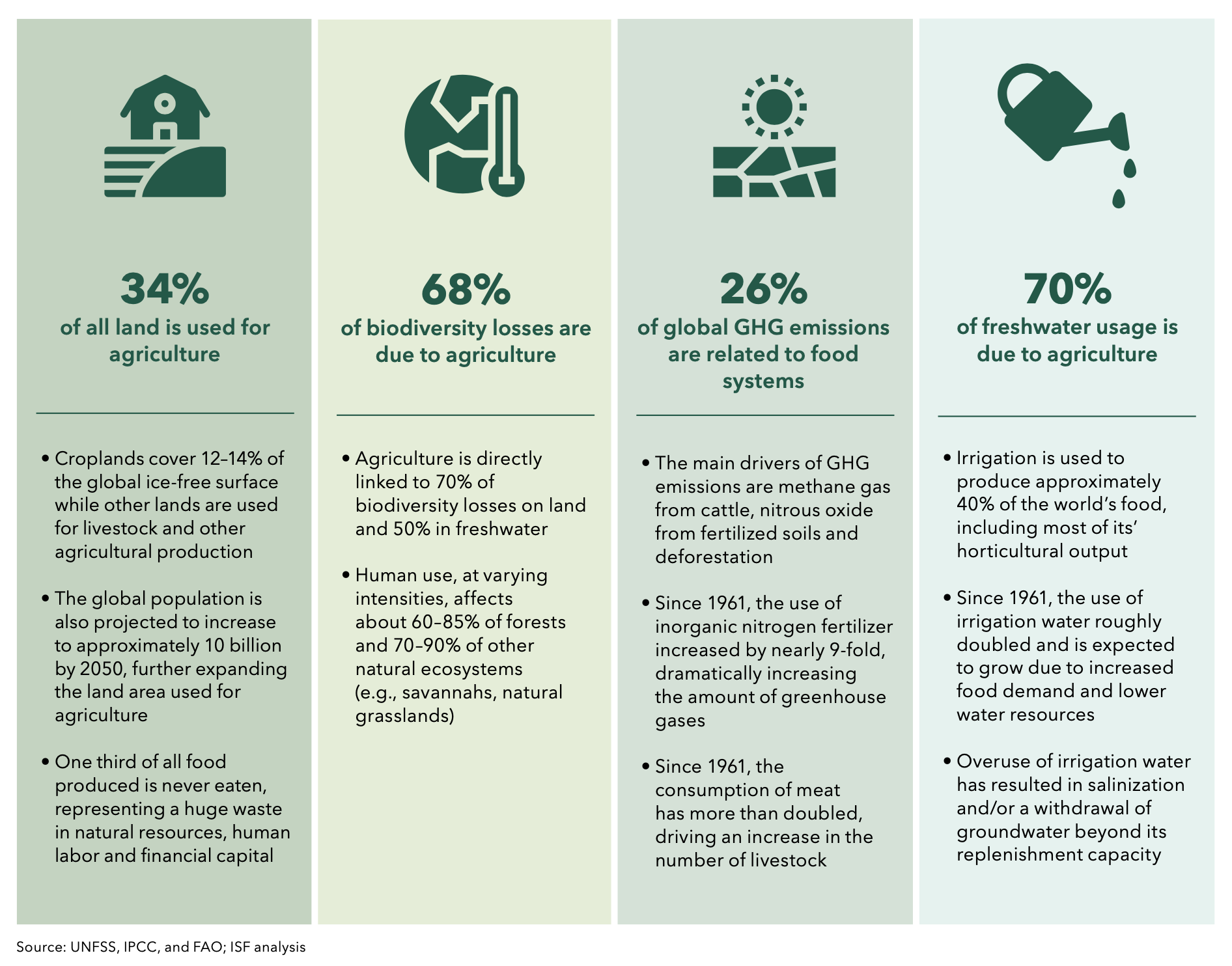

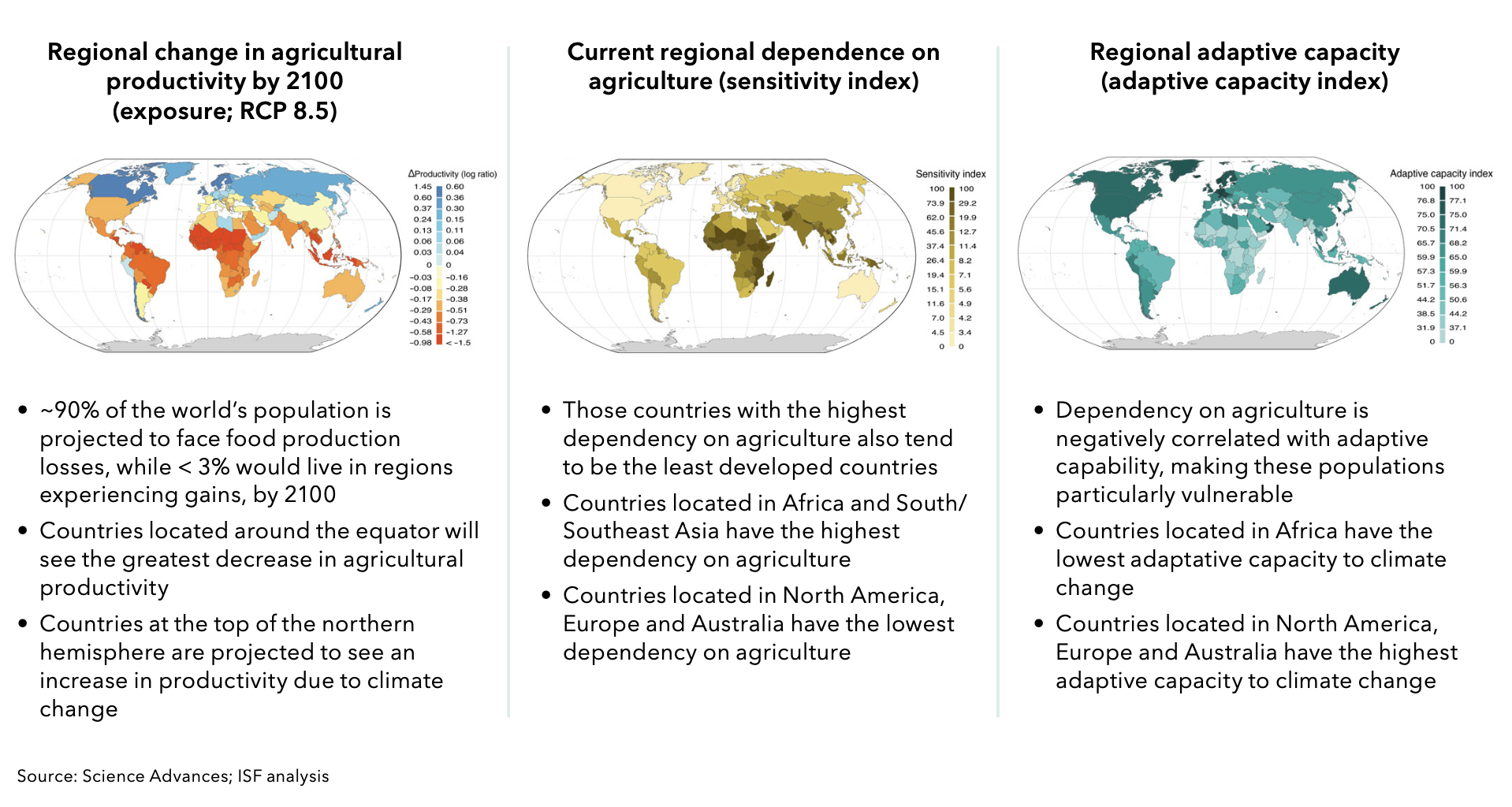

The climate change crisis has the potential to undo decades of progress in global development. According to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) findings, average global temperatures have already warmed by 0.5-0.6°C, relative to 1990 levels, and will likely reach a 2°C increase in the near future. Warming of just 1°C will lead to a worldwide decrease in food production yields, worsening as temperatures rise further.

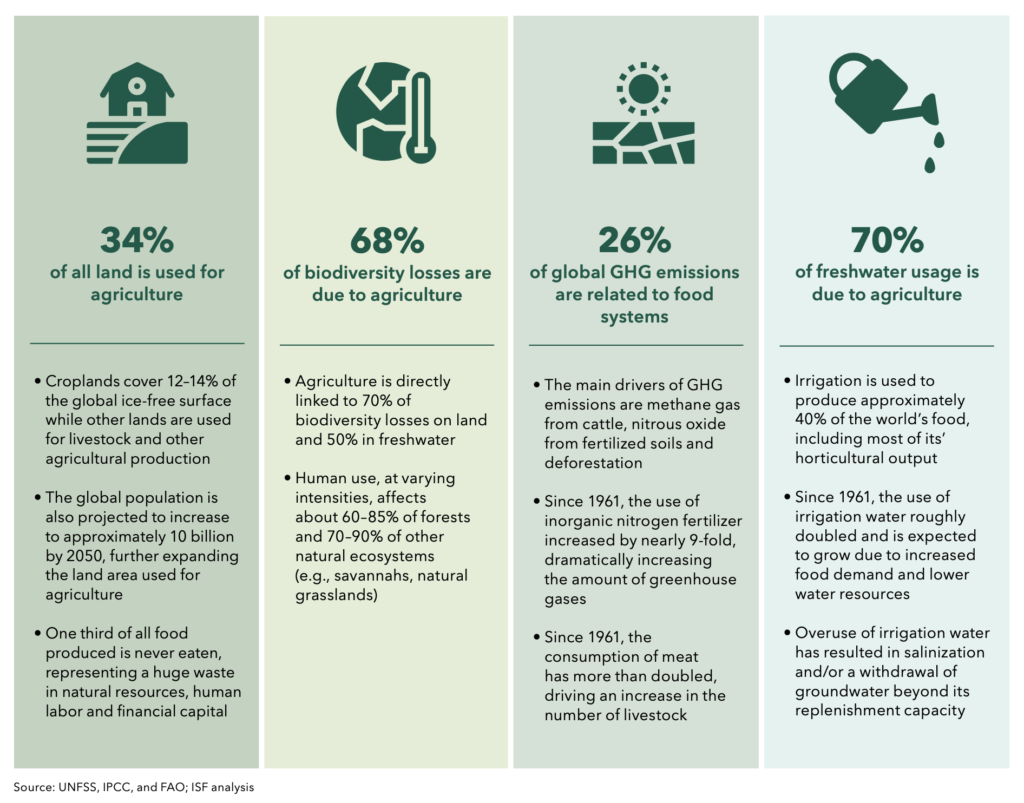

Agriculture is a critical part of this global picture, with food systems being responsible for approximately 26% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.3 Agriculture-related GHG emissions are driven by land use (24%), crop production (27%), livestock and fisheries (31%), and the global food supply chain (18%), resulting from the evolution of our global food system over the past 50 years. Historically, while the Green Revolution increased farm productivity, it also accelerated the negative climate impacts of agriculture.

The Smallholder Link: Contributors or Victims?

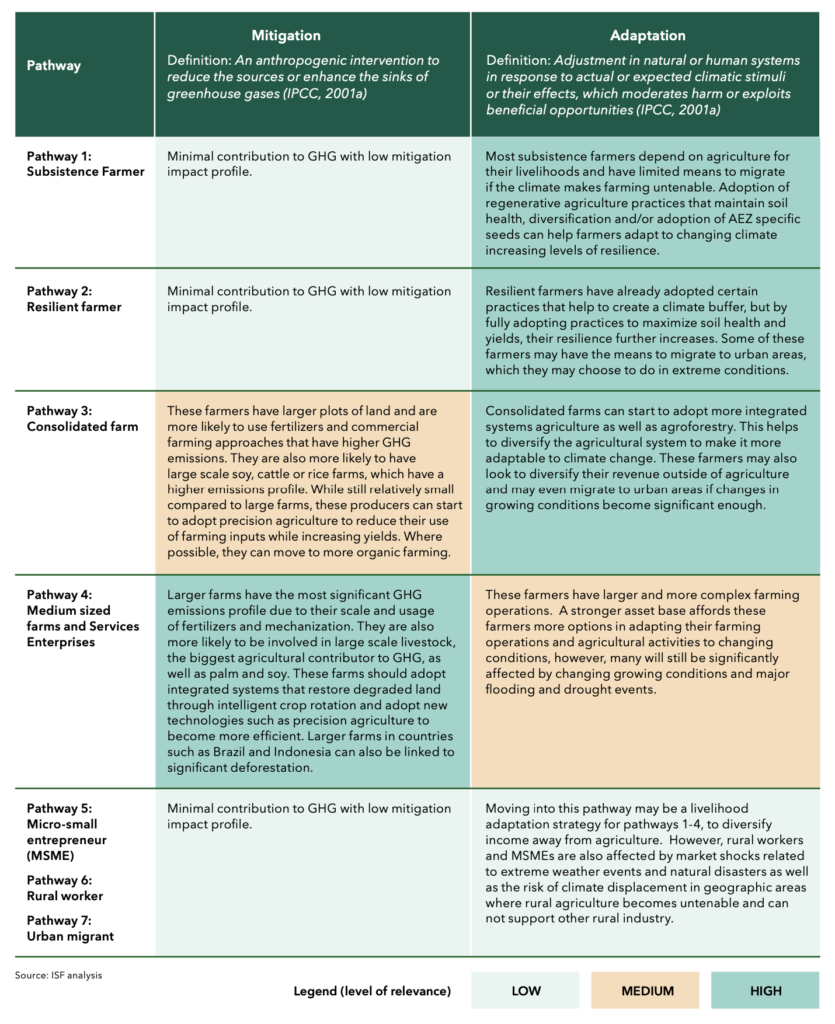

While the agricultural sector as a whole is a major source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the contribution of smallholder farmers is concentrated in select commodities and is relatively small overall. By contrast, large-scale commercial farming contributes heavily to both GHG emissions and deforestation, including in low-income countries.

Relative to commercial agriculture and other sectors, smallholder production systems’ GHG emissions barely register—a fact that should guide the allocation of climate mitigation resources. For example, the average two-acre smallholder farmer in Kenya produces 55 times less carbon than the average American. With this context in mind, it is critical that mitigation efforts for smallholder farmers are focused on farming activities that contribute relatively more GHG emissions or drive land clearing, particularly conversion of wild shrubland, grassland, and virgin forest areas into farms.

Climate Change Impacts on Smallholder Farmers

Despite their low level of contribution to climate change, smallholder farmers are disproportionately impacted by climate variability and climate-related shocks. In the near future, many smallholder farmers will be forced to either leave their land, continue farming in difficult and risk-prone agro-ecological conditions, or adapt what and how they grow. In fact, the World Bank estimates that for 143 million people, climate change will result in land that is no longer arable by 2050, forcing them to migrate to other agricultural areas or to urban areas. At the same time according to a recent International Fund for Agricultural Development study, only 1.7% of climate finance from international financial institutions and other donors is going to climate adaptation activities for smallholder farmers in low-income countries.