Gender Deep Dive

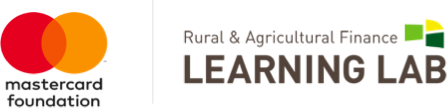

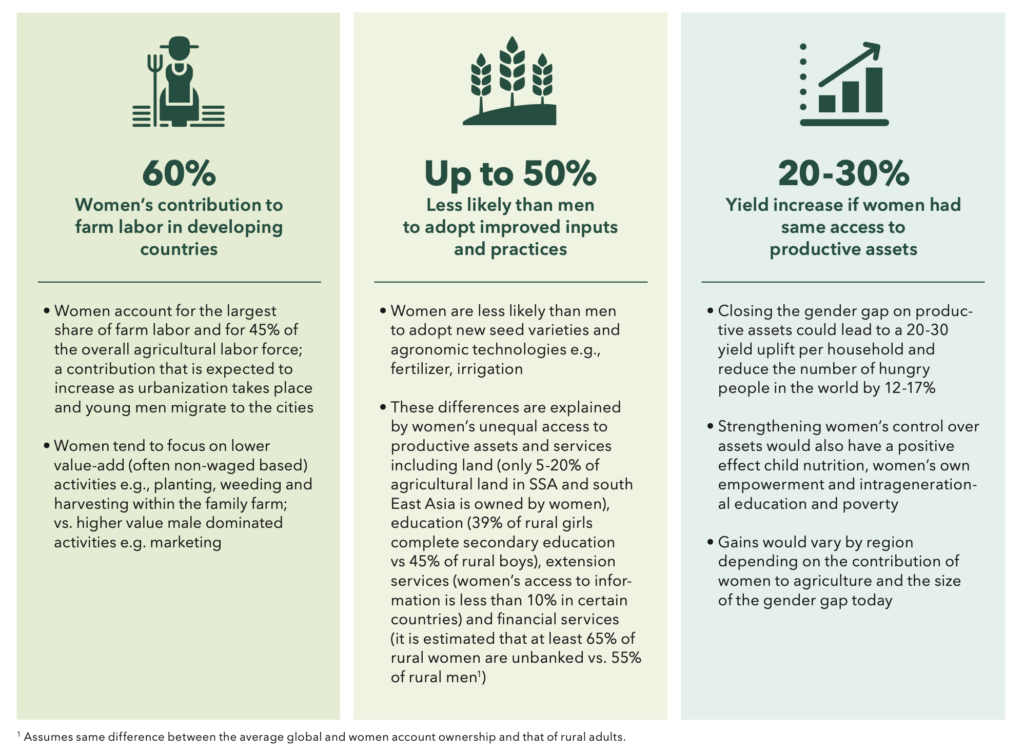

The role of women in agriculture is vital and growing in many countries around the world. Women account for the largest share of farm workers. However, they are significantly less likely to be the owners of the land that they work on or have access to productive assets and services, such as agricultural inputs or extension and training services. It is estimated that if women had equal access to productive assets, yields could increase between 20% and 30% per household. In addition, women’s labor is often non-wage-based, performed at home, and within small-scale agricultural systems.

Many of the same challenges faced by the broader rural population are also faced by women: challenging economics of smallholder farming; relatively underdeveloped rural markets; limited financial resources; and an often weak enabling environment. But rural women face a wider range of structural challenges that financial service providers must address.

- Educational constraints. Women, on average, have lower levels of educational attainment than men. Educational constraints have negative consequences on both the breadth of options and the quality of remunerative opportunities that young women can pursue, on or off the farm. Every additional year of primary school increases girls' eventual wages by 10-20%, while encouraging them to marry later, have fewer children, and making them less vulnerable to violence.

- Socio-cultural constraints. Social and cultural norms can determine the type of economic activities in which women can engage, the people and agencies with whom they can interact, the places they can visit, the time they have available, and the control they can exert over their own capital. For many female smallholder farmers, these social norms exclude them from marketing activities, segregate them into lower value crops or occupations, and prevent them from accessing the capital and networks needed to run a business.

- Legal constraints. Women's access to economic opportunities and labor force participation can be heavily influence by laws and regulation. Financial institutions' emphasis on collateral and asset-based lending means that ownership and control of tangible assets is necessary to unlock finance. Customary laws related to land rights and inheritance that favor male spouses and relatives put women at a great disadvantage. In addition, proof of identity — a key enabler of access to basic services — is often out of reach for women due to restrictive legal requirements, gender-biased policy, or lack of clarity and consistency in policy implementation.

A narrow focus on differences between men and women often masks more important differences between women themselves, including those arising as they transition through various life stages.

At a foundational level, women have the same set of rural transition pathway options as men. They can stay in farming (pathways 1-4), move into rural entrepreneurship services (pathways 4-5), become rural workers (pathway 6), or migrate to urban areas (pathway 7). However, women often face significant barriers in accessing the skills, networks, and assets needed to transition through rural pathways — limiting their agency and mobility across different livelihood strategies.

- Opportunities for young women in subsistence farming households (pathway 1) may include providing labor on the family farm as a way to build skills and work experience they may otherwise be restricted from due to socio-cultural norms. Adult and older women may take on more decision-making responsibilities on the farm, and aim to secure autonomous use of land. Service models that deliver an intensive package of agricultural services will help women break out of subsistence production and reap the benefits of higher productivity and earnings. Access to savings products can help them keep their earnings safe, thus increasing their financial independence.

- The gender gap widens as smallholders move into more intensified agricultural activities (pathway 2), because farm intensification relies heavily on access to productive assets, services, technology, crop diversification, and markets — all of which are particularly challenging for women. Opportunities for women in this pathway include taking on leadership roles in commercial production and accumulating (and eventually owning) productive assets. Service adaptation approaches, particularly around delivery channels, market access, and collateral requirements, are needed to support women in this pathway.

- Most women will struggle to make the transition from farm intensification to land consolidation (pathway 3). Because women are unable (or unwilling) to make investments into land they do not own, the gender gap is greatest in this pathway. Thus, services should be focused on creating opportunities for women to secure leased, joint ownership, or sole ownership of land.

- For women transitioning into formal enterprise (pathway 4), opportunities include owning or taking leadership positions in agricultural and rural SMEs, as well as scaling their business. Providers must address the SME financing gap by adapting collateral and credit risk requirements while also providing business development support and training to fill key skills gaps.

- The dynamics that lead women to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities in rural services (pathway 5) are varied and largely dependent on the wealth of the household. While many rural women pursue micro-entrepreneurship opportunities as an income diversification strategy, women micro-entrepreneurs tend to concentrate more than men in lower value-added sectors or start enterprises with low capital costs and barriers to entry — often relying on informal sources of finance. Start-up and working capital with flexible collateral requirements are necessary to support women in this pathway.

- Women’s need for flexibility to balance their productive and reproductive roles means they are likely to pursue a multi-pronged livelihood strategy, which may include rural employment opportunities (pathway 6), often part time. Because women are often excluded from market activities and do not benefit from the family agricultural income, many prefer to work as labor for other farms where they can have greater control over the income they earn. Reducing the gender gap in wages, improving working conditions, and addressing occupational segregation are necessary to ensure that rural employment can contribute to improving womens’ resilience and agency in this pathway.

In order to create and support economic opportunities for women, services must be designed to address the challenges related to their life stage and the pathways transitions they are pursuing. In the context of the transition pathways, we highlight several approaches emerging in the sector.

- Capacity building approaches to address the human capital gap. These include financial and digital literacy, business development, and soft skills development like building women’s confidence and negotiation skills so that they are better equipped to operate in male-dominated spaces.

- Service adaptation approaches that tailor existing interventions to better suit women’s specific needs. In the case of financial services, particularly credit, an increasing number of providers are experimenting with flexible collateral requirements, alternative data for credit risk assessment, or customized disbursement and repayment structures that fit women’s crop and cash-flow needs.

- Collective action approaches that enable women to circumvent individual constraints. When women are collectivized, they are more likely to gain access to productive assets and formal services, and serving them as a group can increase the economic viability of the service. Collective action leverages women’s own social networks, which is often their most reliable channel for obtaining financial support, employment, and networking opportunities.

- Shared dialogue approaches — involving both men and women — that help challenge powerful gender dynamics. Service providers are increasingly realizing that initiatives that target only women, without tackling the underlying systemic inequalities and gender norms that affect both men and women, are not effective in the long term.

- Gender-based affirmative action approaches to counterbalance structural biases and discrimination, particularly in access to labor markets and entrepreneurship opportunities. Service providers are increasingly applying these approaches both externally (e.g. deploying women-only seed funding programs for female rural entrepreneurs), and internally (e.g. setting quotas to help achieve gender balance in senior management positions).

- Policy-related or enabling environment initiatives to drive structural transformation. These include initiative aimed at changing discriminatory laws that place restrictions on women’s mobility, agency, access to services, and ownership of assets. Of particular importance is tackling the issue of land rights and inheritance laws, and creating enforcement mechanisms that

As emerging economies continue to industrialize and undergo agricultural transformation, women play a crucial role in unlocking rural growth. But achieving gender equality requires sustained and fundamental investments in systemic change — to remove the structural barriers that prevent women from realizing their full potential — as well as in service delivery, to create opportunities for women to build resilient livelihoods.

In this deep dive, we consider women as a specific client segment within the rural pathways model. Building on the broader impact investment theses and concepts in the Pathways to Prosperity report, we believe there are opportunities for:

- Improving our collective understanding of women’s service needs. Most providers continue to underestimate the complexity of serving women, the importance of leveraging their social networks to target services, and the influence social support and educational networks can have on service uptake and impact. There’s a need for the sector to shift away from talking about women in general terms and instead recognize distinct segments of women, according to their pathway and life stage. This recognition can help drive changes in how service providers design and deliver services.

- Driving innovation in market access initiatives. To date, most service adaptation interventions targeting rural women have concentrated on advisory and financial services. While these types of interventions can be effective in closing the gender productivity gap, translating these productivity gains into income gains requires access to markets at fair prices. Because most innovation in market linkages has been private sector-led, it has targeted the most attractive customer segments and therefore failed to reach women, despite their high potential for impact. Donors and investors have an opportunity to put in place the right incentives, supporting service providers in adapting their current models to reach beyond the standard customers.

- Aligning capital investment with capital needs of service delivery. Rural women tend to require a more intensive, higher-touch package of services than the “standard” customer. This, coupled with often smaller transaction values, means the economics of serving female smallholder farmers can be particularly challenging. The potential differences in the underlying profitability means that service providers will have different capital needs, with a larger number of provider models with sub-commercial or grant-aligned profitability profiles that are better suited for donor or impact-driven capital.

- Engaging across sectors to coordinate action on gender-transformative initiatives. The complex and multi-dimensional nature of gender inequality requires cross-cutting approaches that address the intersections between rural women’s agricultural and non-agricultural, financial and non-financial, productive and reproductive needs. With a unified view of the various dynamics that affect rural women’s transition pathways — and how specific service models can support these transitions — government, private sector, and civil society actors can better engage in concerted, targeted actions.