Definition of “youth”: In this analysis, we define youth as individuals between the ages of 15 and 24. This definition is in line with those used by IFAD, the World Bank, and the ILO, allowing for comparability across global datasets and literature. We recognize that it differs with definitions used by others, particularly that used in much of sub-Saharan Africa and by the African Union (15-35 years of age).

Youth Deep Dive

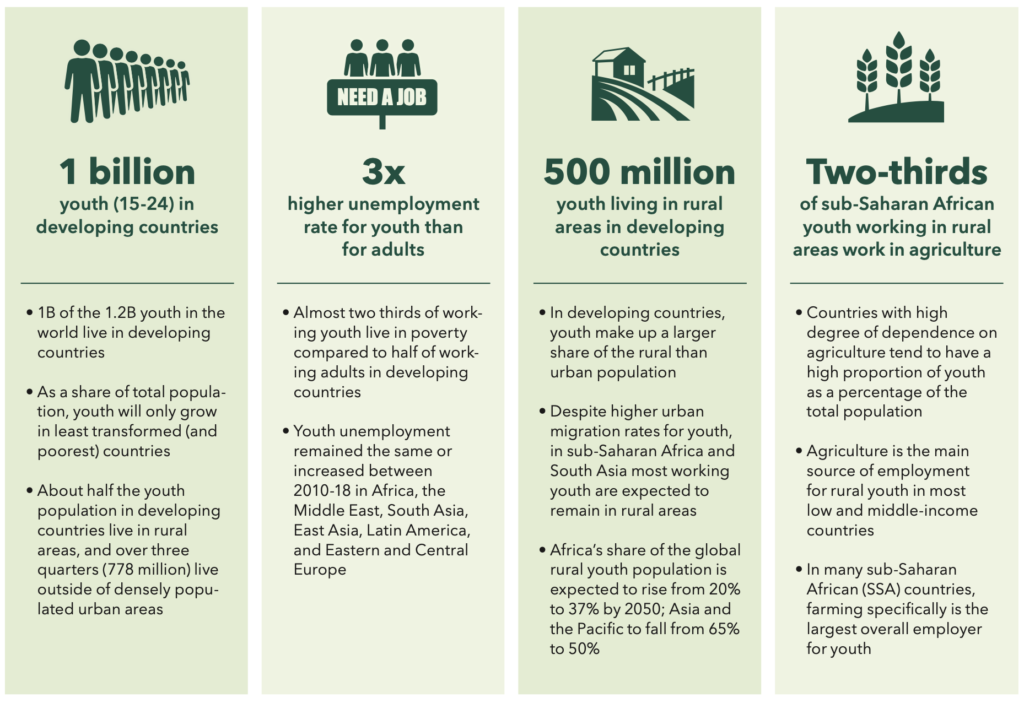

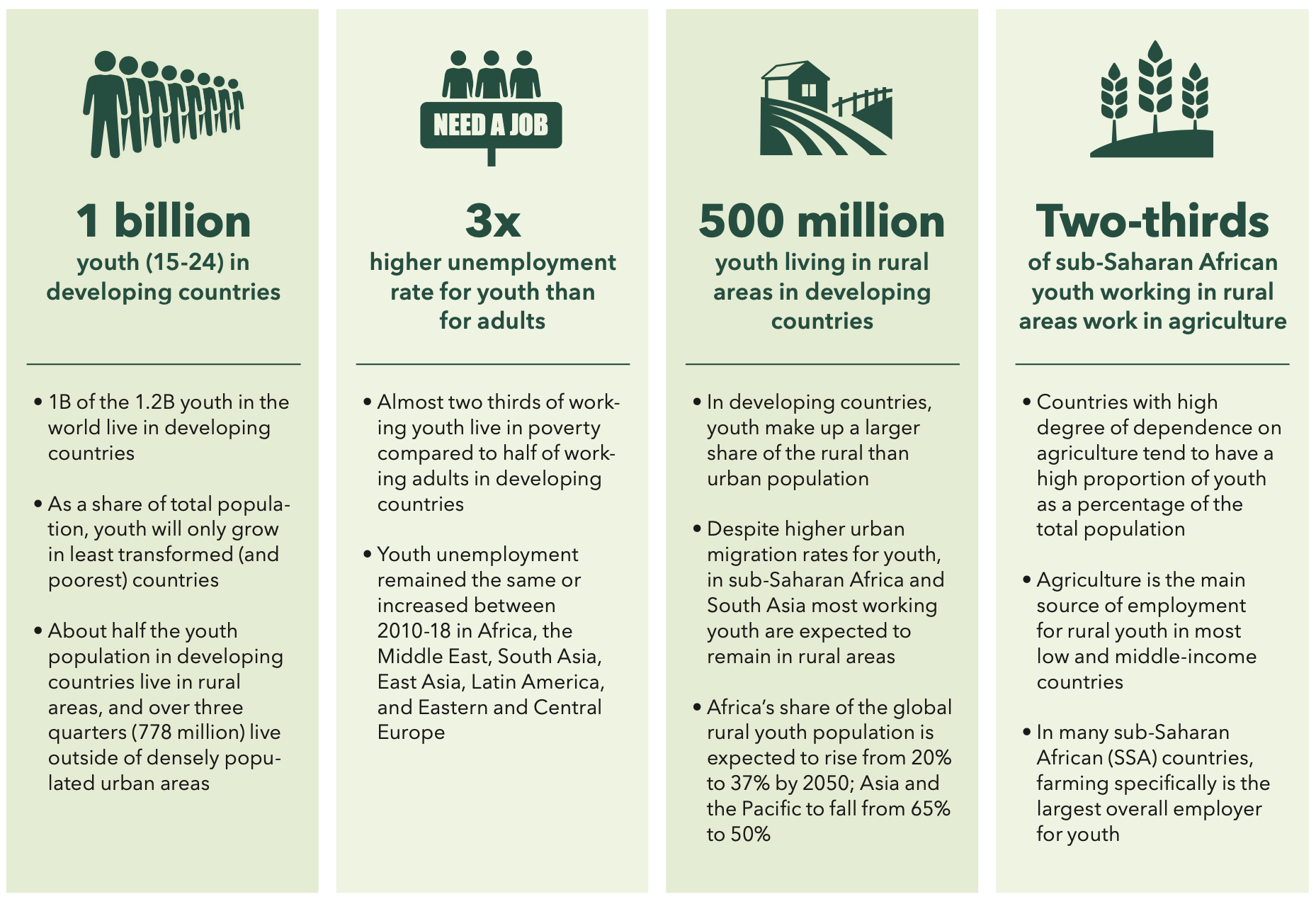

There are 1 billion youth living in developing countries. The youth population in these countries is growing faster than in higher income countries, bringing to light major challenges around gainful employment prospects. The challenge is particularly significant in rural areas where youth account for up to 60% of the population (and 45% of the workforce) and where poverty rates are higher than in urban areas. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, it is expected that most youth will continue to work on family farms and in household businesses in the next five years; only one in four youth will find waged employment, and a fraction of those jobs will be in the formal economy.

Many of of the same challenges faced by the broader rural population are also faced by youth: challenging economics of smallholder farming; relatively underdeveloped rural markets; limited financial resources; and an often weak enabling environment.

In addition to these challenges, youth face unique obstacles and service requirements that providers must address:

- Mobility and urban migration: Youth tend to be more mobile than older adults, moving between urban and rural areas, formal and informal employment, and inside or outside of agriculture. This movement is primarily driven by the lack of opportunities within rural areas. For service providers to design appropriate interventions, they must screen the needs of youth simultaneously across multiple pathways.

- Assets: Relative to older adults, youth are significantly less likely to own or manage agricultural holdings, including land and medium or large enterprises. This is often due to a variety of interlinked factors, including lack of access to finance, as well as legal and communal land ownership restrictions.

- Family of origin: The familial starting point of youth has a very strong impact on their livelihood trajectory. Youth born into farming households are most likely to end up being employed in farming. The opposite holds true for youth born into non-farming households.

- Gender: Female youth face unique challenges due to the more limited options available to them. The result is that rural young women often lag behind men in educational attainment, asset ownership, economic participation, and productivity. For a more detailed gender analysis, please see Section 7 – Outcome area deep dive: Gender.

At a foundational level, youth have the same set of rural transition pathway options as non-youth. They can stay in farming (pathways 1-4), move into rural entrepreneurship services (pathway 4-5), become rural workers (pathway 6), or migrate to urban areas (pathway 7). However, based on their unique life stage, skills, networks, and assets, youth have different needs, opportunities, and challenges than non-youth — leading them to transition differently through the rural pathways model.

- For youth in subsistence farming households (pathway 1) the main barriers are land access and the challenging economics of farming in general. Opportunities for youth include contributing labor and taking a leadership role in adopting practices that help advance the family farm. Youths’ higher adoption rates of innovative practices and technologies present an opportunity to help drive farm professionalization. In the long term, improving the family farm can create opportunities for youth to own assets, including land.

- For youth seeking to play a role in more resilient and consolidated farms (pathways 2 and 3), their higher adoption rates of new technologies can help them drive progress either on family farms or in self-owned farms. Youth service needs include tailored financial products to allow youth to purchase or lease land, as well as access more complex farming inputs and assets. Success stories for youth in pathways 2 and 3 can serve to improve the attractiveness of agriculture for youth more broadly.

- Many youth seek entrepreneurial opportunities in rural service entrepreneurship (pathway 5). Formal opportunities include becoming agents within established value chains; informal opportunities include involvement in agricultural and non-agricultural ventures. Youth-run micro-enterprises can play a key role in driving progress in pathways 1-4; conversely, progress in pathways 1-4 can stimulate demand for micro-enterprises from which youth can benefit.

- For youth working in rural areas (pathway 6), consistent employment can be challenging. It often requires youth to move between rural, peri-urban, and urban areas; between agriculture and non-agricultural employment; and between formal and informal sectors to generate sufficient income. Service needs include directly building the employability of youth, and indirectly supporting the growth of farming and service enterprises to create more demand for youth employment.

In order to create opportunities for youth, services need to match the demographic changes and challenges related to the pathway transitions they are pursuing.

Broadly speaking, services provided to youth fall into either supply-side or demand-side interventions — focused, respectively, on improving the employability of and expanding employment opportunities for youth. Most of the focus has been on supply-side interventions.

However, as the issue of rural youth employment becomes more pressing, service providers are starting to implement a range of approaches, including:

- Employment priming approaches, which build the capabilities of youth for employment and entrepreneurship opportunities. Examples include Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and entrepreneurship models.

- Service adaptation approaches, which tailor existing interventions to better suit the specific needs and circumstances of youth. This includes tailoring financial products to make them more feasible for youth (e.g., by decreasing collateral requirements).

- Value chain-specific approaches, whereby youth gain employment opportunities within broader value chain models. Examples include internship and traineeship opportunities offered by offered by service providers and offtakers.

- Multi-stakeholder approaches, which bring together multiple stakeholders—often from the public and private sectors—to integrate a combination of the above-listed interventions. Crucially, multi-stakeholder approaches can link supply-focused interventions with demand-focused efforts to ensure that youth, once their capabilities have been boosted, have real employment opportunities.

- Broader policy and enabling environment initiatives, which focus on strengthening the enabling environment and spurring broad economic development to create employment opportunities for youth.

Click here for a more detailed breakdown of youth-specific opportunities and service considerations in each pathway.

The issue of youth livelihoods in rural areas will become an increasingly important one in the years to come. In this deep dive, we have attempted to illustrate how youth can be considered as a specific client segment within the rural pathways model.

Building on the broader impact investment theses and concepts in this Pathways to Prosperity report, we believe there are opportunities for:

Practitioners and thought leaders

to deepen research into the unique needs and challenges of youth as they pursue different livelihood pathways.

Existing service providers

to put a youth lens on their service provision that takes into account these challenges and dynamics.

Governments, donors, and NGOs

to further innovate multi-stakeholder or multi-dimensional programs that deal with youth-specific challenges in a way that is closely linked to more structured employment and livelihood opportunities.